Computing the Meanings of Words in Reading: Cooperative Division of Labor Between Visual and Phonological Processes

Background

“Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” ———— George E. P. Box

Although humans have been reading for several thousand years and studying reading for more than a century, the mechanisms governing the acquisition, use and breakdown of this skill continue to be the subject of considerable interest and controversy…

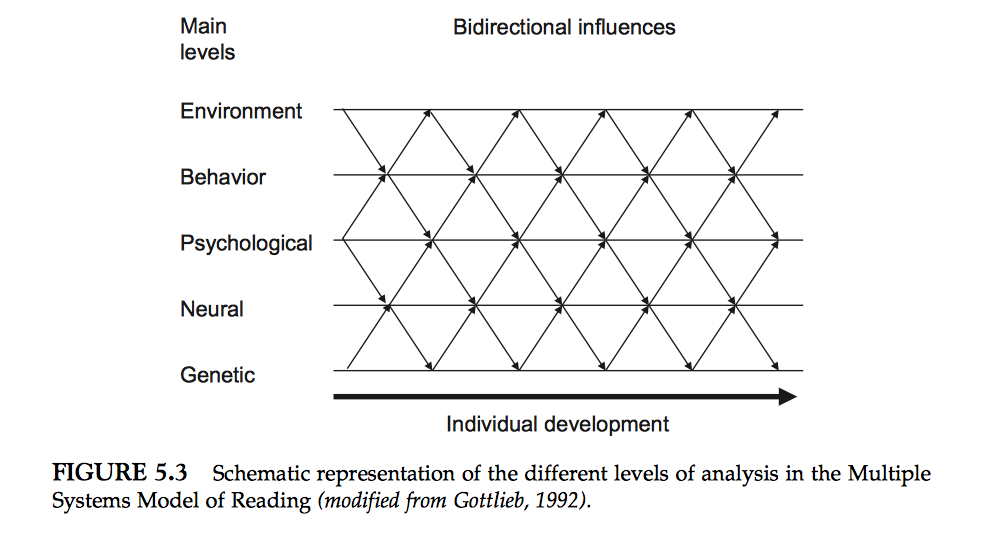

Reading development could be considered as a complex system across different levels in which other complex systems embedded.

Why it is important? The practical reasons is about how reading should be taught. See wikipedia for the Reading Wars.

Researchers in reading research investigate both typical and atypical reading development. Two levels: word reading and reading comprehension. Here we focus on word reading.

Computational Model of Reading

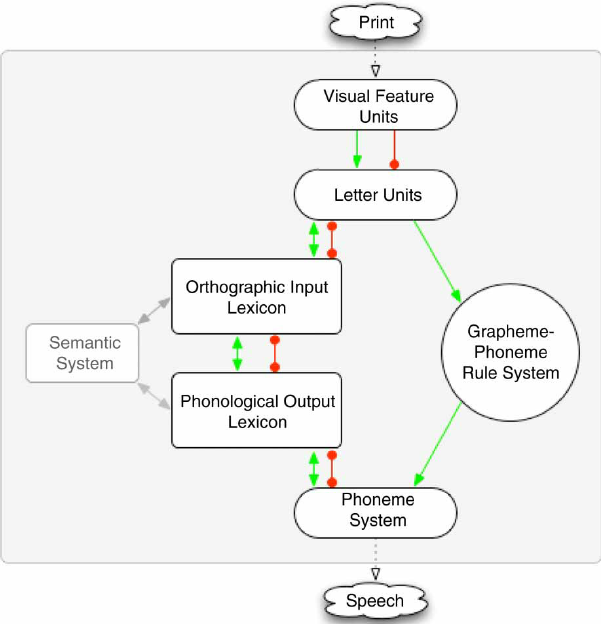

There are many theories relating to development of word reading but fewer can be simulated computationally. See here for the Dual Route Cascaded (DRC) Model of Visual Word Recognition and Reading Aloud as an example.

The DRC model is largely inspired by clinical observations. Based on the philosophy of symbolism, this model argues against connectionism for which artificial neural networks are important tools.

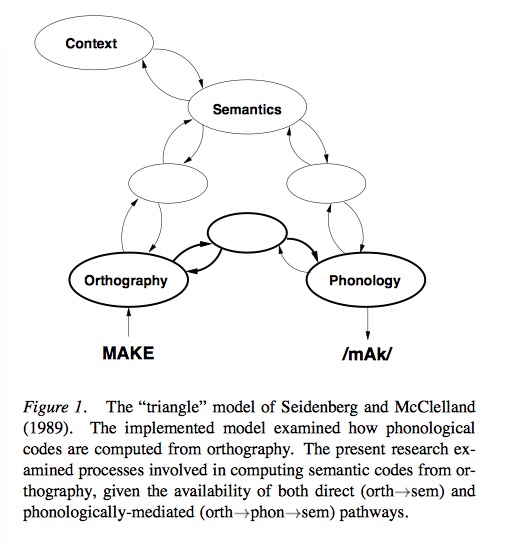

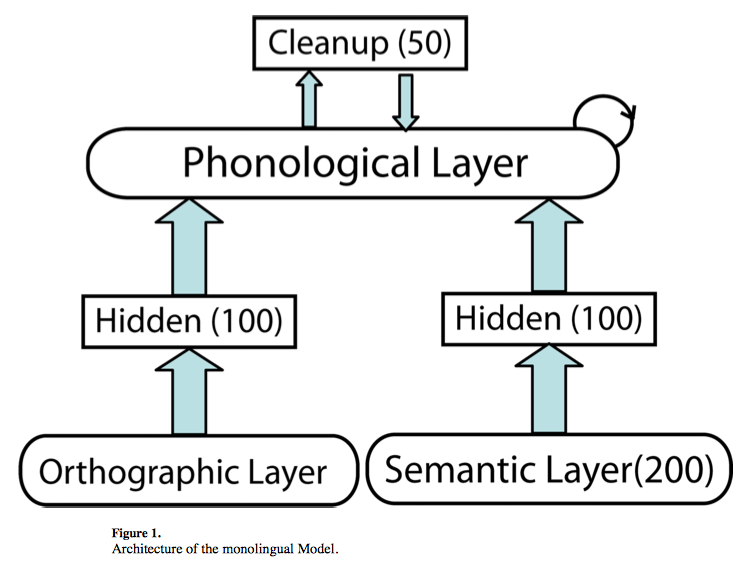

Now look at this connectionist model:

The key point is that it assumes some general architecture, algorithm, or other principles in modeling reading development.

“Smith’s argument about the difficulties involved in using phonological mediation rests on the assumption that spelling-sound correspondences are encoded by rules. Connectionist models such as Seidenberg and McClelland’s (1989) subsequently provided an alternative in which the correspondences are encoded by weights on connections between units involved in the orthography-phonology mapping.”

Some Issues

1) Localist vs Distributed Representations: accessing vs computing;

2) Attractor structures: A network has an attractor basin when it develops stable points in activation space, and has the tendency to pull nearby points toward the stable attractor points. In this way, partial or degraded patterns of activity are driven towards more stable, familiar representations;

3) Supervised Learning;

4) Catastrophic Interference: Training a simple feedforward network on one set of patterns followed by training the network on a second set of patterns resulted in unlearning of the first set.

Model Details

1) Training Corpus: 6,103 monosyllabic words;

2) Semantic Representations: A total of 1,989 semantic features were generated from WordNet online semantic database to encode the 6,103 words;

3) Phonological Representations: 25 phonological features x 8 phoneme slots = 200 units were used to encode the each CCCVCCCC word, with vowel centering to minimize the “dispersion” problem;

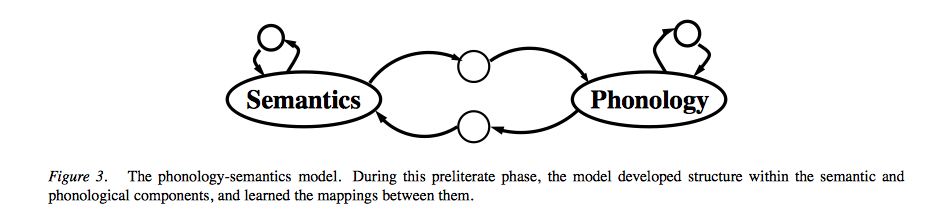

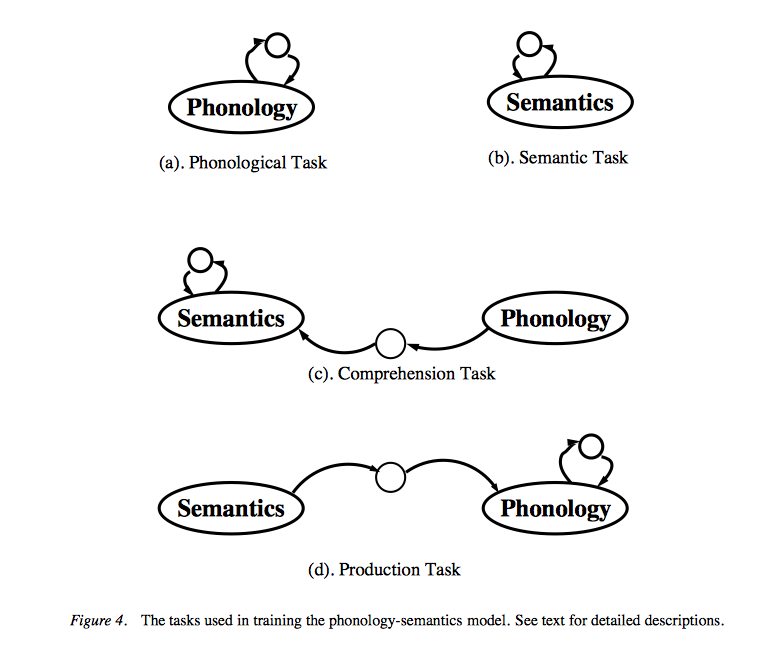

4) The Phonology-Semantics Model:

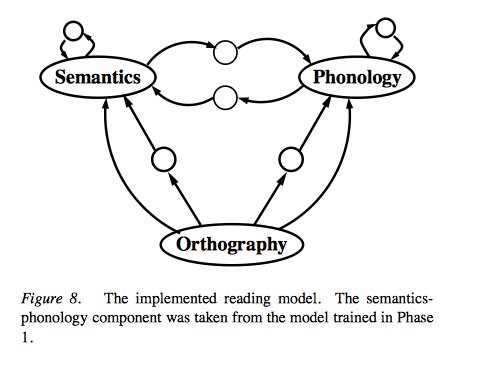

5) The Reading Model:

6) Orthographic Representations: 26 features corresponding to the letters of the alphabet X 10 slots = 260 units -> 111 units (slot-based localist)

Division of Labor

The Model’s Basic Properties

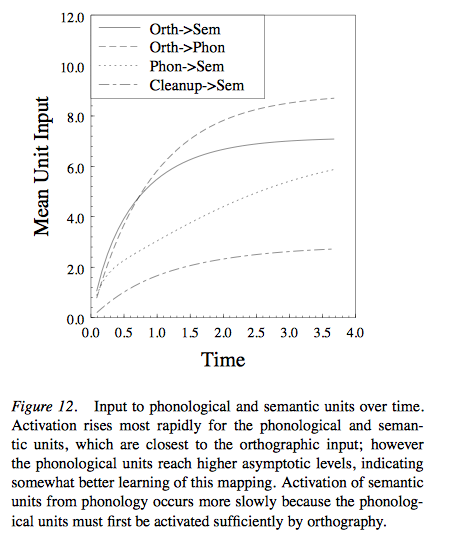

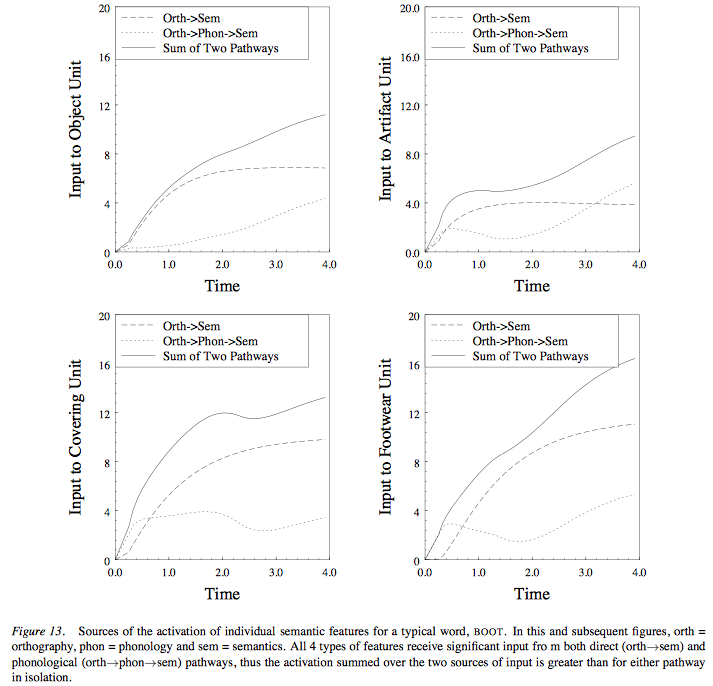

1) Activation of meaning from multiple sources;

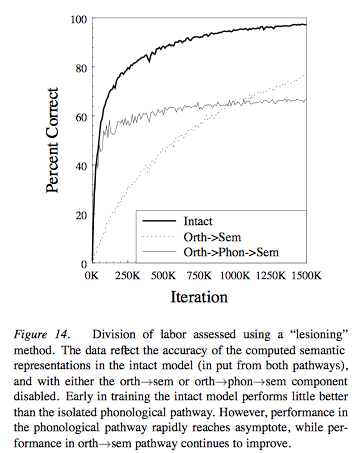

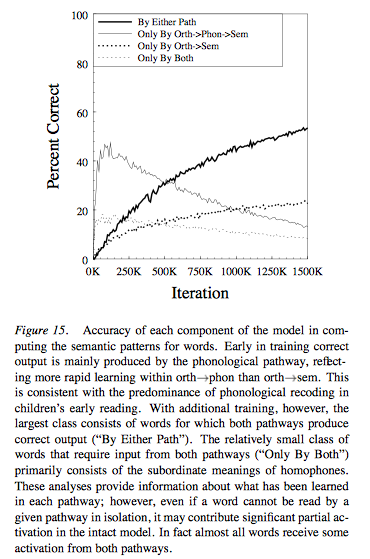

2) Course of learning;

3) Precedence of phonological pathway in acquisition;

4) Development of the orth -> sem pathway;

5) Capacity of the orth -> sem pathway;

6) Co-operative computation of meaning.

What’s more?

1) No Panacea! Every model has its own advantage and disadvantage and none can explain everything of reading behavior.

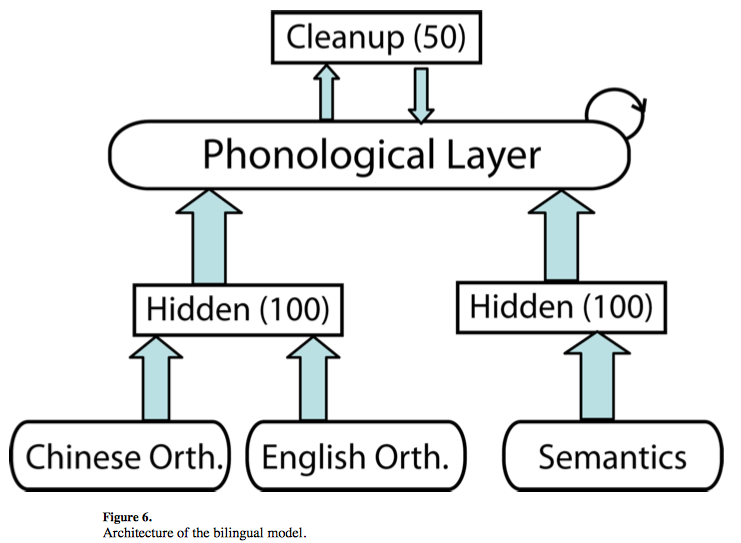

2) Modeling Chinese and bilingual:

References

Harm, M. W., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2004) Computing the Meanings of Words in Reading: Cooperative Division of Labor Between Visual and Phonological Processes. Psychological Review, 111(3), 662-720.

Cortese, M. J., & Balota, D. A. (2012) Visual Word Recognition in Skilled Adult Readers. in The Cambridge Handbook of Psycholinguistics (pp.159-185).

Yang J., McCandliss B.D., Shu H., & Zevin, J. D. (2009) Simulating language-specific and language-general effects in a statistical learning model of Chinese reading. Journal of Memory and Language, 61(2), 238–257.

Yang, J., Shu, H., McCandliss, B. D., & Zevin, J. D. (2013) Orthographic influences on division of labor in learning to read Chinese and English: insights from computational modeling. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 16(2), 354–366.